Sara Brand

Job Title: Founding General Partner of True Wealth Ventures

Years in the tech industry: 20+

On the True Wealth Ventures mission:

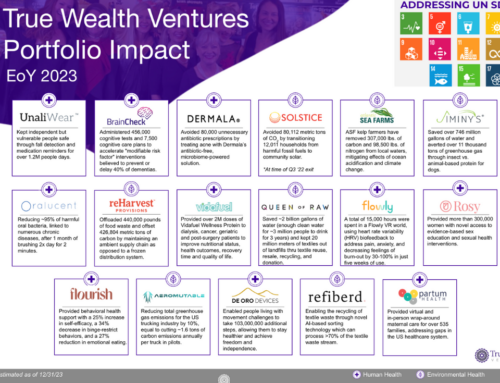

We are an early stage venture capital investment fund that invests in women led companies in the sustainable consumer and consumer health markets, as a financial thesis to deliver top-tier returns to our investors. Companies with more women at the leadership table perform significantly better financially whether they are Fortune 500 companies or smaller venture-capital backed startups. We are investing in markets where women make the vast majority of purchase decisions (women are making 85% of consumer purchases and 80% of healthcare decisions) and expecting an additional financial return from that, since gender diversity games should have an advantage in understanding those customer and market needs, so they can design products that meet those needs more effectively and go to market and service those customers more efficiently.

Our strategy is to invest capital in strong women entrepreneurs with solutions to improve environmental and human health so they can scale those products and technologies and provide outsized financial returns to our investors, while being role models for future founders and investors to innovate and invest.

On ‘traditional’ beginnings — the home front:

My dad was a mechanical engineer, which is very typical for women going into mechanical engineering. It’s almost always that their dads were mechanical engineers, so they were exposed to it and knew it was something that they could even go do. My parents always encouraged me academically, but I grew up in a very traditional household where my dad was the sole breadwinner and my mom stayed home and raised the kids and volunteered. I was told and thought I could do anything, but I didn’t actually have any role models of how to do that.

On education — studies in a male-dominated academic field:

It’s so hard for me to say [what affect gender had on my education] since I got my bachelors, masters and PhD in mechanical engineering. I never knew any differently, so I have nothing with which to compare the experience. I know I faced some discrimination, mainly from the teaching assistants in labs who were from countries where women really didn’t have equal rights, but for the most part… the reason why I loved math and engineering so much is that you didn’t have to worry about bias in the grade because it was either the right answer or it wasn’t!

On entering the workplace — and future strategies:

The one gender-specific, self-induced challenge I remember is feeling like I only had about 5–7 years to significantly advance my career and pay rate in order to make getting a PhD worthwhile before having kids (like catching up to the pay scale if I had started working right out on undergrad or getting a masters). I knew I wanted to have the option to have kids, and I believed I had to be high enough up in an organization to be valuable enough that I could continue working. No one ever told me this, nor did I ever talk to anyone about it.

On early experiences in Silicon Valley:

I got my PhD out in Berkeley while working at tech companies in Silicon Valley, and then I worked in the semiconductor/electronics industry in Silicon Valley between technical roles, management consulting, venture capital and operational rolls. I was the only woman at the VC firm and on the client and project teams during all those years. I was really blind to any gender related experiences because all my education was in mechanical engineering, so I was used to very male-dominated environments and didn’t know any differently. Now that I look back on it, I see a lot of experiences I had that were unique to being a woman, but I navigated it just fine and generally thought of it as an advantage. That being said, I wouldn’t want my daughter or up-and-coming women to have to deal with what I dealt with, and nor would I deal with it as gracefully now if I rewound time and hit play again.

On aligning with ‘the other VC woman in Texas’:

How I came to meet True Wealth Ventures General Partner Kerry Rupp is both funny and telling. When I decided to leave my corporate tech job to start this fund and began to discuss it with people, I was quickly introduced by several folks to Kerry as “the other woman in venture capital” in Austin. Now that we look back at it, we think she may have been “the other VC woman in Texas!”

At the time, Kerry was the CEO of DreamIt Ventures, one of the top tier accelerators in the U.S. and the most active investor in health tech. They had just started DreamIt Athena, the first women entrepreneur focused program at a top-tier accelerator, so she was very aware of the issues and opportunities of funding women entrepreneurs.

On how her VC company came to work with 80% female investors, and whether a specifically women-forward business model is now part of the brand/mission statement:

It was certainly not our original mission to get over 80%, or even a majority, of our investors women. In fact, we expected quite the opposite of that given that we had been told when we first started fundraising that women were more risk averse, didn’t invest in venture, didn’t understand capital call structures, etc. and that they focused on managing their philanthropic investments but had wealth managers to manage their financial investments. When we conducted the first close of our fund, we didn’t even really notice that half of our investors were women until those women started introducing us to their friends and colleagues that they thought had the capacity to invest and would resonate with the fund’s strategy. Several of our women investors hosted gatherings for us, and we saw that the fund’s investment strategy and us, as rare women GPs [GPs=General Partners who manage the Fund’s investments], was really resonating with women. So, then we started doubling down on women investors and the network effect snowballed.

We ended up with over 80% of our investors being women, either single women or the woman from a couple, family office or foundation who drove the investment decision. This is unprecedented in the venture capital industry and was picked up by several national platforms including Forbes and the Wall Street Journal. I would say that it is part of our mission now since it really is critical to changing the ecosystem. The further I get into the industry and see both the challenges and the opportunities, I think it’s women investors who are going to be the impetus to getting more venture dollars to women entrepreneurs.

On fund-raising challenges for women founders:

It’s really hard to say if any of our challenges were because we were women, but I will say that it is a major challenge for the women entrepreneurs in the VC industry. It’s estimated that only 1% of venture capital firm partners who are making investment decisions (e.g., setting the term sheets, taking board seats, etc.) are women. To start a new venture capital fund, LPs (the Limited Partners who invest in funds) typically require a track record. VC funds are typically 10 year funds, so it takes several women working together at a fund for over 10 years to develop a track record of working together before spinning out to start their own fund. Those numbers obviously don’t bode well for fast or significant change in the venture-capital industry.

On advocates (versus ‘mentors’):

I was very lucky to find “advocates” along my career path. I am not a huge fan of mentoring as I think it is typically pretty sloppy and inefficient, but advocates are senior to you in an organization so can tell you about opportunities, push you to do them, put your name on the table in conversations you are not a part of, etc. These people have been more important to my career than mentors ever could be. They were all men due to the nature of the companies/firms I was at, but they were great!

On being a mentor:

I used to mentor women before starting True Wealth Ventures (up to 3 at a time), and I valued using a formal mentoring structure so there were clear agendas, timeframes, a reason for the match, etc. I think that’s an important role of a mentor — making sure the mentee drives the relationship and has clear goals of what they want to get out of it.

In my current role, I am working with our portfolio companies, sitting on the boards and that could be seen sometimes as a mentoring type of relationship. The Fund looks at an average of 10 new companies a week, so I simply do not have time to mentor people outside of our portfolio anymore and try to do more speaking engagements to reach a broader audience that way.

On increased opportunity for women in business, and female entrepreneurs — or the lack thereof:

While I think that there is a lot more attention on this issue in the press, certainly over the last year, I don’t think the landscape has gotten more encouraging. People I speak with are always surprised that the numbers are still as bad as they are. I think everyone assumes that with such a spotlight on the industry and the issues that it would naturally be getting better, but it’s not yet — with either the number of women in the venture-capital firms making the investment decisions or the women led companies getting venture funding. Unfortunately, we’re seeing the pendulum swing the other way a bit with the sexual harassment issues in the industry leading to a lot of the traditional VCs being coached to not even meet with women entrepreneurs because it’s a risk to their reputation.

On surveying the landscape to measure how opportunities for career advancement for women has changed over the course of her career:

I don’t have any data that it has changed, but I do know that awareness of the issues has changed for the better. I think we are now waiting for that awareness to translate into a better work climate. For instance, the numbers of women graduating from engineering school hasn’t changed significantly since when I graduated, but there’s a lot more awareness now about how important it is to get women engaged in STEM activities starting an elementary and middle school in order to get them into engineering school to improve the numbers.

Likewise there’s a lot more effort over the last few years to recruit technical women into the workplace, but we haven’t really seen the retention numbers change and that’s potentially due to a largely unchanged climate or opportunity for career advancement. If you look at the McKinsey Women in the Workplace surveys and study data, there’s more commitment to gender equity and greater awareness of what some of the issues are, but there’s a lack of understanding on how to actually change the culture. Therefore, the outcomes of women not getting the job offer, not getting the promotions, not getting the stretch assignments, not getting the help to navigate the politics, etc. haven’t changed. I was just reading an updated study/survey of 600+ women in health tech, and those women are more pessimistic than last year regarding how long it will take to reach gender parity in the workplace. According to Ernst and Young, the countdown to gender parity is still more than 200 years away. Even though awareness has increased, I think it is the sluggish pace of change which is causing this pessimism.

I don’t have the data around this, but what I believe is changing is senior women’s awareness that they need to drive the change. I think a lot of experienced women thought that the issues had gone away and are looking back on their careers and realizing that they have not and that if they don’t do something about it nobody else will or can.

On her perception of what the landscape looks like to young men and women entering the tech workplace:

I believe most young men and women entering tech workplaces today believe that the gender-based obstacles have been removed, and that’s part of the challenge. I think millennial women have largely thought they wouldn’t have to deal with those obstacles, so when they don’t get a promotion and their male colleague do, they take it personally since they think that bias is gone. This can really exacerbate confidence issues — especially when the largest gap in promotion rates is still the first step up to manager (entry-level women are 18 percent less likely to be promoted than their male peers) when confidence levels are already lower without the work experience. The bias can be pretty subtle too, so often male colleagues don’t see it since they don’t think it’s there to begin with or experience it.

The good thing is that the awareness and education of bias is increasing, so women can be more aware of it and learn about the tools to overcome it, along with their male colleagues who can help them as well.

On the generational shift amongst men:

I think that younger men have lost a lot of the biases, but that can sometimes make changing the tech culture even more challenging since they don’t see bias existing in the workplace and often aren’t on the receiving end of those sometimes subtle situations. Unfortunately, I often see men not realizing it’s an issue (or still an issue) until their daughters are old enough to get into a relevant workplace situation, and that’s the first time they really become aware.

On how women can contribute towards lasting change within the industry:

I think having more positive role models and success stories is both the quickest and most powerful way to make lasting change. There is this saying that you can’t be it if you can’t see it, and that’s the strategy we are taking: to fund women entrepreneurs who are doing great things and helping them get to wildly successful scale so others can see that they can do it too. Those succesful women come into increased wealth and reinvest, and the virtuous cycle begins in that sense too. I think living by your actions speaks louder than any words, so that’s what we’re doing with the fund — putting our money where our mouth is and creating great success stories that others can follow.

Read the full piece on Sara T. Brand.